Aupa Etxebeste!

Aupa Etxebeste! released in 2005 was the first feature film made in Euskara (Basque Language) in over a decade (since 1993), and is a comedy about keeping up appearances. The film became a watershed moment for Basque-language cinema, as its success brought visibility and legitimacy to productions made in Euskera.

The Etxebeste family is well respected in their small Basque town, and are proprietors of a Txapel (traditional Basque cap or beret) factory and are citizens of influence. But on the eve of their summer holiday to Marbella, they discover that they’re broke. The neighbors mustn’t find out and so they devise a plan which finds them hiding in their flat for the duration…

2005, directed by Asier Altuna & Telmo Esnal, 97 min, color, in Basque with English subtitles.

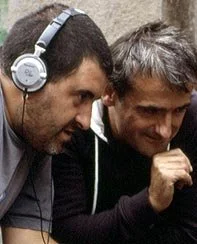

Asier Altuna, Telmo Esnal

Asier Altuna (Bergara, Gipuzkoa. 1969) and Telmo Esnal (Zarautz. Gipuzkoa, 1967) co-directed, in 2005, Aupa Etxebeste!, which competed in New Directors and won the Audience Award in San Sebastian. In 2016 they contributed with the segment Iraila to the omnibus film Kalebegiak, screened at the Velodrome. Single-handed, Altuna has competed in San Sebastian’s Official Selection with Bertsolari (2011, out of competition) and Amama (2015), winner of the Irizar Award. In 2018 he participated in the omnibus film Gure Oroitzapenak, screened in Zinemira. His lastes film Karmele (2025) premiered at the San Sebastian Film Festival.

For his part, Esnal has directed Urte berri on, amona! (2011) which participated in New Directors and Dantza (2018), which won the Global in Progress Award in 2017 and was presented in San Sebastian’s Official Selection the following year.

CAST

Patricio Etxebeste - Ramon Agirre

Maria Luisa - Elena Irureta

Luziano - Paco Sagarzazu

Iñaki - Iban Garate

Axun - Iñake Irastorza

Exenarro - Patxi Gonzalez

Julian - Jose Mari Agirretxe

Juan Kruz - Felipe Barandiaran

Maite - Ane Sanchez

Lapurra-1 - Guillermo Toledo

Lapurra-2 - Luis Tosar

Udaltzaina - Anjel Alkain

Excerpt from the book Basque Cinema: A Cultural and Political History

by Rob Stone and María Pilar Rodríguez (2015).

Aupa Etxebeste! is an example of contemporary Basque cinema of sentiment and was the first full-length feature to be filmed in Euskara since 1993. Like many of their generation, Altuna and Esnal graduated from the Kimuak initiative having co-directed the shorts Txotx (1997) about the Basque cider ritual and 40 ezetz (Forty says no, 1999) which describes a murder over cloning oxen in the sport of idi demak (stone dragging). Altuna also made Topeka (Ram fight, 2004) for Kimuak, which prefigures Aupa Etxebeste! by indicating frustration with the stubborn rigidity of the community of citizens. In Topeka a throng of male spectators argue their bets and rally rams into conflict, but the impulse spreads amongst the men, who head-butt each other senseless. Sarcastic and profound, in just three minutes Topek reflects upon myths, symbols, gender roles and customs and exudes clear-eyed frustration with tradition. Aupa Etxebeste! retains its caustic wit and allusive political sensibility about Basque heritage in a comic tale of a Basque businessman and political hopeful named Patrizio Etxebeste (Ramón Agirre), whose company makes the classic Basque berets and is quickly going bust. Compelled to retain his status in the community, Etxebeste pretends to take his family away for their annual summer holiday but actually hides them at home for four weeks until able to fake their return. Aupa Etxebeste! is prescient about pending worldwide economic crisis and its local repercussions, while the parochial and familial response to a homecoming engenders universal sentiment of longing and belonging. By situating its tiny Basque village within a global economic downturn, it also exudes the melancholia common to Brassed Off! (Mark Herman, 1996), SubUrbia (Richard Linklater, 1996), The Full Monty (Peter Cattaneo, 1997) and the similarly plotted L’emploi du temps (Time Out, Laurent Cantet, 2001). At first the family has to overcome food shortages by trapping pigeons, and the inability to flush the noisy toilet except in synch with that of the neighbor, but there are poignant punchlines to most comic set-pieces. For example, the feast of a neighbor’s cat provokes the grandfather’s memories of such fare during the duress of the Spanish Civil War, when not one was left uneaten. Before he can dine, however, their idyll is broken into by two silent intruders, who opportunistically scoff the roasted feline before making off with the grandfather’s stash of banknotes. Most pointedly, the burglars communicate entirely in grunts and glances, despite being played by Luis Tosar and Guillermo Toledo, two of Spain’s most popular film stars. That these low-life invaders of the home(land) are non-Basques is a witty enough comment on radical Basque nationalism; but the fact that Tosar and Toledo are also muted is a gag – a literal one – played upon Spanish film stars given bit parts in Basque language film.

Aupa Etxebeste! exemplifies the Basque cinema of sentiment because it is both local and global, enacting a worldwide economic crisis upon the tiny stage of an apartment in Gipuzkoa, in which a bravura tracking shot passes repeatedly through its walls to provide a literal cross-section of the declining middle class and whose cast actually takes a Brechtian bow after the final fade to black. Yet the sentiment that emerges from these people who cannot leave a room is not bleak and vicious like that of El ángel exterminador (The Exterminating Angel, Luis Bruñuel, 1962). Instead, the family rediscovers love and respect as the film promotes catharsis through empathy, both displaying and undermining the differences of Basqueness by showing these beret-wearing, Euskara-speaking folk to be citizens of the same world as us. Sentiment in Aupa Etxebeste! therefore plays what Murray Smith following Ronald de Sousa has called “a strategic role in our behavior, by directing our attention and thinking toward particular aspects of situations and deflecting our attention and thinking toward particular aspects of situations and deflecting them from other aspects. The point here is that emotion is integrated with perception, attention and cognition, not implacably opposed to any of them. Indeed, the cinema of sentiment both entails and illustrates this process that calls our attention to sentiment as a way of thinking towards perception. This illustrates Sorenson’s claim that the community of sentiment “must also be exposed to changes in a new context characterized by the increased salience of globalization and the transnational relations that go with it.” It is an ongoing process which demands that political convictions are no longer preordained from well-defined party affiliations. Aupa Etxebeste! has a poignant, temporary resolution that chimes with the final male strip show of The Full Monty and the open-top bus concert of Brassed Off!: the family’s pretend return to the village is scuppered by them running out of petrol and their car with them inside being ignominiously carried home on a transporter, which interrupts the local parade full of Basque folk music and dancing figures and becomes an applauded float. Thus, against a backdrop of Basque heritage, local tradition and global uncertainty, Aupa Etxebeste! illustrates Sorenson’s view that collective identity, ‘whether religious, ethnic, cultural or social, is of much reduced significance in the new context [but that] these various modalities of collective identity certainly seem to continue to be important for many people.” Moreover, in involving the parade of Basque traditions as a temporary panacea for global problems, it rejects any notion of that with Anthony D. Smith terms ‘a memoryless scientific “culture” held together solely by the political will and economic interest’ with little or no emotional appeal. Instead, it suggests that people can take on any number of new identities without losing or discarding what they already have, thereby illustrating the challenge set by Sorenson ‘to discover the reference points of collective identity that are currently gaining rather than losing importance. As an illustration of Basques in the world, Aupa Etxebeste! reveals the world in the Basque Country.